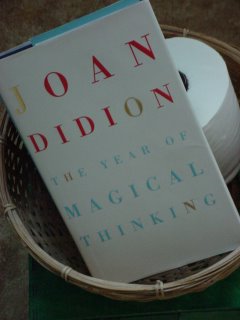

The Year Of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

Despite living a world in which we are daily exposed to the news and images of death, nothing it seems can prepare us for the up-close loss of a loved one.

Even where this occurs after a period of illness, where in theory affairs are put in order and appropriate provisions made, the consuming void of grief is enormous, devastating, and nearly always underestimated by those caught in its maw.

It is sometimes said that how we react in the face of real adversity is the key to knowing our true character. No matter how we present ourselves to the world in life, our bearing under the weight of such finality is who we really are.

The sudden death of Joan Didion’s husband, the writer and critic, John Gregory Dunne, in their

The facts are starkly presented without dramatic device or adornment. Married for nearly forty years and occasionally collaborating on screenplays, they lived and worked in the same apartment and had barely been separated for more than a few days in that time.

Their daughter Quintana, a grown woman in her thirties, had been admitted to hospital suffering from what appeared to be flu but accelerated into pneumonia, septic shock and coma.

After visiting Quintana in the intensive care suite of their local hospital, Didion describes the moment when the world she knew abruptly halted after Dunne suffered a massive heart attack and died.

Life changes in the instant.

You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.

The question of self-pity.”

Her journalistic instincts to get on top of the facts to rationalise what happened quickly come unstuck. No amount of medical research about the heart condition that felled her husband or the chronology contained in the coroner’s report nor still yet, the weighty academic studies of loss and mourning and its psychological repercussions, gain her a toehold back to the “normal” world from which she had been irrevocably dislodged.

Assiduously combing through the facts, trying to control the information becomes an ever more desperate scramble; fingers clinging to the ledge of reason.

If knowledge is normally equated with power, in the face of death, its usefulness is overrated. No amount of understanding the cause and effect can change the outcome or lend “meaning” to her partner’s absence.

In trying to restart her life she attempts a conjuring trick, creating an illusion that her husband will be coming home. The trade-off for this precarious navigation between “moving on" and confabulating a twilight world in which she refuses to dispose of her husband’s shoes because he will need them when he comes back, is that she must avoid or block out the myriad reminders of what she’s lost.

Like a tightrope walker fearing to look anywhere but straight ahead, streets, restaurants, dates, books and people are rendered off limits lest she be sideswiped by what Didion calls the vortex. Happier times are now too painful to bear, once cherished memories now a desolate territory tainted by “what if?” and “if only…”

In doing so, she swims against the undertow of the medical profession’s detachment, feeling resentment at what she sees as a high-handed, closed ranks approach to decision making for her care. The passages where mother sits with her unconscious offspring tethered to her life support are charged and incredibly poignant. Any reader who has a child will appreciate the utter nightmare of this situation and hope it's somewhere we never have to be.

When she tells an unconscious Quintana “You’re safe. I’m here” Didion reluctantly recognises with a sense of rising panic and horror that such instinctual words of comfort and reassurance are emptied of their promise, rendered meaningless when up against the prospect of death. Nothing is guaranteed anymore.

The tremendous effort involved in writing such an account, with its raw, honest clarity is obvious. Her constant gnawing over facts and potential portents of what was about to happen to both her husband and daughter becomes obsessive bordering on the deranged.

Didion acknowledges her reluctance to finishing the account. Whilst writing it she is able to keep Dunne from being dead. Finishing the book begins the process of letting go, of moving on with her life but not his.

The unbelievably cruel postscript not mentioned in these pages was that although Quintana apparently recovered, she would later die following complications from acute pancreatitis.

“Time is the school in which we learn,

Time is the fire in which we burn.”