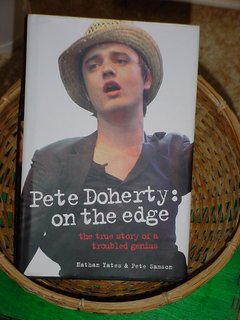

Pete Doherty

Pete Doherty: on the edge

Nathan Yates & Pete Samson

John Blake

ISBN1844541762

In an age when people are famous for being famous rather than actually doing something, there’s an pronounced tendency to tout the latest flavour of the month as a being genius. This is true of the rock press and even more so in the tabloids. It’s no surprise then that Yates and Simpson of The Daily Mirror should find Pete Doherty to be not only a genius but that most overused cliché, a troubled genius.

From this bottom of the Doherty barrel scraping, we can all agree he’s troubled but we see scant evidence of much else. We learn insightful gems such as Pete read voraciously, that he was prone to Byronic brooding and that Lady Caroline Lamb was the Kate Moss of her day.

Oh and he was a bit like William Blake because of his fondness for referring to

Dodgy comparisons are tossed about like so many used syringes. Orwell, Dickinson (Emily not David), Wilde, de Sade and other literary heavyweights are frequently invoked although the authors never quite explain how Pete’s writing as opposed to his lifestyle, gives them a run for their money.

After wading through endless pages of tittle-tattle about his drug habit and sex life, one begins to empathise with Libertine Carl Barat’s decision to injure himself by repeatedly smashing his skull off a sink when forced to hole up with his ex-mate in order to write songs for the next album.

Music is not what this book is concerned with. The merits of The Libertines and Babyshambles are barely alluded to, reduced to walk-on parts in a stupefied trail from

Reading this tosh brings it home how someone somewhere in the industry is probably itching to put together the Pete Doherty “best of” compilation. Posthumously of course. Then the hacks will really be able to go to town with the superlatives, adding “tragic” and “legend” to the already overlong list. I bet they can’t wait and if Doherty carries on like he is, then they won’t have too much longer to hang about with those cliché-ridden obits.